Recorded on September 21, 2021

Ward | Sood | Lieven | McGlynn | Chernenko: “The Return of the Taliban”

Recorded on September 21, 2021

Ward | Sood | Lieven | McGlynn | Chernenko: “The Return of the Taliban”

September 9, 2021

Can be seen by clicking on the YouTube link above.

Published by ORF-America on September 11, 2021

(Part of its series at https://orfamerica.org/newresearch/the-united-states-in-afghanistan-an-indian-perspective)

As dawn broke on 31st August, Afghans awoke to a sense of growing uncertainty and anxiety about what comes next. The last US evacuation flight had taken off hours earlier and on board were Ambassador Ross Wilson and Maj Gen Chris Donahue, closing the chapter that began on 7th October 2001 when US launched Op Enduring Freedom with air strikes against the Taliban.

In 2001, nobody could imagine this is how it would end 20 years later. There is no getting away from the fact that the images of the messy exit will stay etched in our collective conscious for a long time, just as the iconic image of US marines being evacuated from Saigon by a helicopter from a rooftop in April 1975 have never been forgotten.

Even though the US intervention ended ignominiously on President Joe Biden’s watch, there were a series of cumulative mistakes by each of his three predecessors – Presidents Donald Trump, Barack Obama and George W Bush, that contributed to this outcome.

Later in the day, Biden came out with a defiant speech, defending both the decision to exit and also the manner in which the exit was conducted. He claimed that the Doha Agreement signed on 29th February last year when Trump was in the White House, left him with the “choice between leaving or escalating”. What Biden ignored was that after having called it ‘a bad deal’, he had retained Ambassador Zalmay Khalilzad, the architect of the deal, in the same role. His own inclination had always been to exit and as Obama’s Vice President, he had opposed the ‘surge’ but was over-ruled by Obama and the generals.

He maintained, “I am not going to extend this forever war and I was not extending a forever exit”. However, as many have pointed out, US did not fight a twenty year war, it merely fought a one year war, twenty times over. Biden insisted that there was no way of doing a more orderly exit because had he started it earlier while the civil war was still going on, there would still have been a rush for the airport and it would have led to a crisis of confidence in the government, making it a difficult and dangerous mission. He is perhaps right in that the evacuation only commenced after Kabul fell and President Ashraf Ghani fled the country on 15th August. Yet, it overlooks the fact that as late as 23rd July when he spoke on the phone with Ghani, it is clear that neither leader foresaw the impending collapse though the trends were visible.

Biden identified two key lessons, “setting missions with clear achievable goals and staying focused on fundamental national security interests”. These are valid lessons and he was pointing to the beginning of Op Enduring Freedom. Even while denying it, the US and the international community had embarked on a nation-building exercise in 2001 because Bush’s global war on terror demanded it. Preventing a return of Taliban demanded building a new constitutional democratic state, or so the Americans believed. However, even as the Taliban found sanctuary and safe-havens in Pakistan that enabled them to regroup and re-establish their financing mechanisms, US got distracted with the war in Iraq from 2003 onwards.

The Pakistan ISI resumed their old game with the US, running with the hares and hunting with the hounds, emerging as the front-line state partnering the US in Afghanistan while subverting US efforts by aiding and abetting the Taliban and the Haqqani network as they unleashed a spate of IED attacks and suicide bombings in Afghanistan, aimed at undermining the Afghan government and drawing the US forces into a counter-insurgency from what had initially been a counter-terrorism mission. Every US commander beginning with Gen Dan McNeill in 2008 has acknowledged sooner or later that it is impossible to defeat an insurgency that enjoys safe-havens.

In public testimony, US CJSC Admiral Mike Mullen called the Haqqani network “a veritable arm of the ISI”. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, on a visit to Islamabad, warned her hosts, “You can’t keep snakes in your backyard and expect them only to bite your neighbours”. Feeling boxed in by the generals, Obama finally gave into demands for a ‘surge’ in US troop presence on the assurance that things would turn around in 18 months. He raised US troop levels to over 100000 but also announced the drawdown that ended combat operations in end-2014. President Karzai warned that the US was fighting the wrong enemy in the wrong place and Carlotta Gall came out with a provocatively titled book, “The Wrong Enemy”, highlighting failures of US military strategy. Obama’s change of policy was evident in the opening of the Taliban’s office in Doha, marking the beginning of their legitimisation from an insurgent force to a political actor.

Trump called out Pakistan, tweeting that US had “foolishly given Pakistan more than $33 billion over the last 15 years and they have given us nothing but lies and deceit, thinking of our leaders as fools and giving safe haven to terrorists”. By mid-2018, he reversed policy and authorised direct negotiations with the Taliban further adding to their international acceptance. By February 2020, the US withdrawal deal in return for safe passage was signed and presented to the international community as a peace deal. The process of legitimisation was complete and the last favour the US did was to ‘persuade’ the Afghan government to release over 5000 Taliban prisoners, adding to its marginalisation.

This was the policy maze that Biden found himself trapped in. He could have tried to change the flawed narrative of ‘forever wars’ or taken action against the safe havens but he chose to cut the Gordian knot by redefining the objective, by declaring that the mission had been accomplished by killing Osama bin Laden and decimating Al Qaeda and assuring the American people that their security could be ensured by over-the-horizon kinetic options. The problem is, it doesn’t smell like victory.

Once Biden set an expiry date for US presence, Taliban began their military operations. The collapse of the Afghan state authority happened like Ernest Hemingway’s explanation of how you go bankrupt – it happens in two ways, first gradually and then suddenly.

The Afghan army had been built on the US model, based on sophisticated reconnaissance units, real time intelligence using drone and aerial surveillance and monitoring, and air support. During the last six years when they had the lead in combat, they had lost over 50000 security forces compared to less than a hundred US and NATO troops killed in action proving their fighting mettle. It is true that there was corruption and this impacted morale but institution building takes time. However, with the withdrawal, especially the contractors, all support systems disappeared. Ammunition replenishment to forward bases dried up as supply chains collapsed. Medical evacuation was no longer feasible. Aircraft, helicopters and drones were grounded. GPS tracking and targeting ended as proprietary software from weapon systems was removed. The soldiers had been trained to fight like an army, not as a guerrilla force, and now, they were crippled. Perhaps the most succinct explanation of the collapse was in the recent op-ed in the New York Times by a three star general of the Afghan army Samy Sabet, “We were betrayed by politics and presidents”.

What happens now? Unlike in other places, wars in Afghanistan become serious when the fighting stops. The Taliban emerged as an Islamist Pashtun force in the 1990s and that remains its DNA. It has again achieved power through military means and not through negotiations. Statements about creating an inclusive and representative government remain vague and ambiguous. How does Taliban manage its relationships with its principal benefactor, the ISI and other collaborators, the foreign militant groups like Al Qaeda, IS-K, IMU, ETIM, TTP etc? How long before the fighting begins again?

Biden has ended America’s ‘longest war’ but peace is yet to appear on the Afghan horizon.

*****

Published in Hindustan Times on September 13, 2021

Twenty years ago, the events of 9/11 changed the world, hurtling it into a new era. Even today, historians label it the post-9/11 era. A ‘global war on terror’ was launched. That era has ended and presumably, so has America’s ‘global war on terror’.

Historians prefer a date to bookend, but that depends on who you ask. On 31st August, the US concluded its withdrawal from Afghanistan, taking comfort in having undertaken the largest airlift evacuation but it was the Taliban that was celebrating their victory.

In 2001, US boasted of an invincible military. In 1998, Secretary of State Madeleine Albright had famously described America as “the indispensable nation”. Explaining why US used military power, she said, “We stand tall and we see further than other countries into the future, and we see the danger here to all of us”.

Back then, North Atlantic treaty Organisation (NATO) operations in the Balkans had stunned the world with the display of the military superiority, using laser guided precision weapons with seamless digital integration of Command, Control, Communications, Computers, Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (C4ISR) capabilities. Russian economy had shrunk to the size of that of Portugal. China was just entering the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

Today, it is a different world. The age of strategic rivalry has returned. Taliban, ably helped by Pakistan, US’s ‘frontline ally’ in its ‘global war on terror’, has badly dented the notion of US invincibility. Despite President Joe Biden’s efforts in recent months to reassure allies that “America is back”, there is a wariness about both US commitment and its competence. The images of people hanging on to the C-17 Globemaster as it taxied for take-off at Kabul will remain as enduring as the image of last American helicopter out of Saigon in April 1975, hours before the Viet Cong stormed the city.

In 2001, the US embarked on two operations. The first was against Taliban and Al Qaeda but it was never successfully completed. Gen Pervez Musharraf who had been threatened into cooperating, pleaded that he couldn’t unless he got the Pakistan army officials – serving and retired – who had been advising and working with the Taliban. US played ball and the Kunduz airlift began in November. It lasted nearly a week and between 2000 and 3000 people were airlifted, including not just the Pakistanis but also a number of other senior Taliban and other jihadi leaders.

The second botch up was in December when Osama bin Laden was cornered in Tora Bora. Brigadier James Mattis, deployed in Kandahar (later Defence Secretary Gen Mattis) asked for reinforcements to surround the area but CentCom commander Gen Tommy Franks declined as he was preoccupied with finalising the operational plans for the Iraq invasion for Rumsfeld. The task was subcontracted to a local Afghan commander Hazrat Ali, and bin Laden, with his group, manged to escape across the Durand Line.

The outcome became apparent in 2005, once the US was distracted with Iraq and the Taliban had regrouped to begin their insurgency with suicide attacks and improvised explosive devices (IEDs).

In parallel, the US launched a second operation in Afghanistan with the Bonn Conference. The objective was to rebuild Afghanistan as a democratic, functioning state that would not play host to, or allow its territory to be used by, terrorist groups. Except that the US never accepted the idea of ‘nation building’ and the UN mission in Kabul, headed by veteran Algerian diplomat Lakhdar Brahimi was only permitted ‘a light footprint’.

The cardinal sin was that the US (and allied) military forces got increasingly drawn from a counter-terrorism operation into a counter-insurgency operation that meant winning ‘hearts and minds’, a challenge for a foreign force that lacked empathy for a conservative, tribal society and its traditions. Counter-insurgency should have been done by the local forces but the newly created Afghan administration headed by President Hamid Karzai had neither the resources nor the agency and, in the process, became ‘a puppet regime’ and US forces represented ‘foreign occupation’.

The die was cast once the process of legitimisation of Taliban began with the opening of their Doha office in 2013. US exit was a given; the only question was when. Once direct negotiations began in 2018, the timeline became apparent. The US withdrawal deal signed in Doha in February 2020 was sold to the world as a ‘peace deal’, with a ‘reformed’ Taliban, a Taliban 2.0.

If there were any illusions about a Taliban 2.0, these were dispelled with the announcement of the new interim government on September 7. To underline that this was now a Pakistani enterprise, the chief of the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) Lt Gen Faiz Hameed visited Kabul on September 4 for confabulations with different actors.

The Doha group that had been the political face of the Taliban engaging with the international community has been relegated to the second rung. Many of the key fighting units on the ground have not found place in the new dispensation, presumably because they would be less amenable to foreign direction. The Quetta shura finds strong representation, especially those who were also around in the 1990s Taliban government.

The clear winners are the Haqqanis who have long been known for their proximity to the ISI. Not only does Sirajuddin Haqqani control the all-powerful Interior Ministry, his family and friends enjoy key positions in Intelligence, Refugees, Communications and the Borders ministries. Most important, Haqqanis will control the appointment of governors to seven eastern provinces (Loya Paktia) that border Pakistan.

A nascent resistance movement centred in Panjshir valley has petered out. Demonstrations in cities that were drawing international condemnation have now been banned. Yet, even those countries that had promoted the idea of a Taliban 2.0 seem to be hesitant about rushing forward with political and diplomatic recognition.

America has ended its ‘forever war’; Afghans are preparing for a long winter.

*****

September 15, 2021

India Akrita Reyar | Chief Editor (Digital) Updated Sep 15, 2021 | 11:24 IST

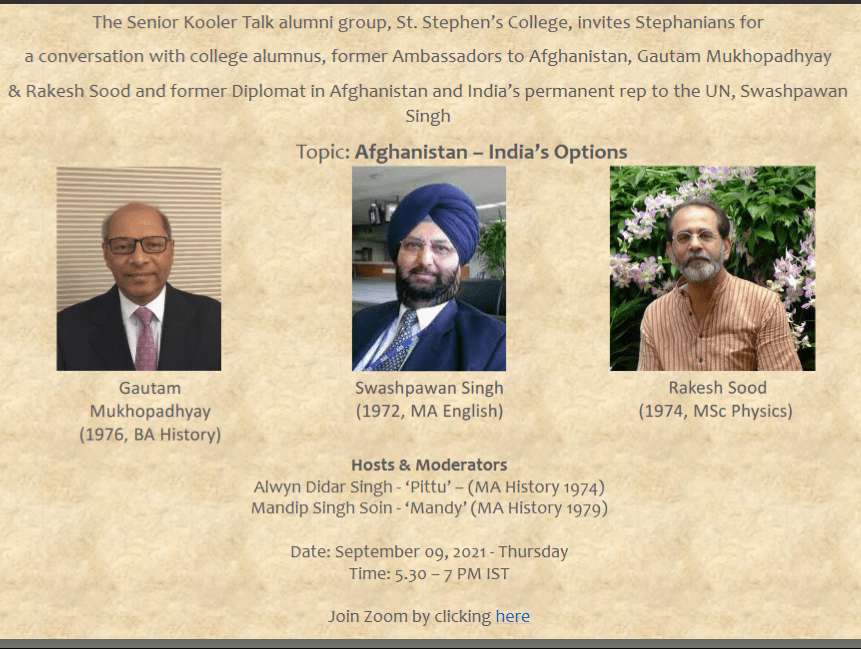

India’s former ambassador to Afghanistan Rakesh Sood | Photo Credit: Twitter

India’s former ambassador to Afghanistan Rakesh Sood | Photo Credit: Twitter

Exactly two decades after 9/11, life came a full circle in Afghanistan as well. Its experiment with democracy crumbled as the Taliban got a virtual walkover after quickly overwhelming the country’s military and administrative structure. US Secretary of State Antony Blinken said that by January 2021, the Taliban was in its strongest military position and America had the smallest number of US forces in 20 years there. US President Biden, therefore, faced a choice between ending the war or escalating it, which would have required a substantial deployment of forces.

Considering the dramatically changed dynamics in our neighbourhood, Akrita Reyar of Timesnownews.com spoke with India’s former ambassador to Afghanistan Rakesh Sood about the current circumstances and the road ahead.

Akrita Reyar: The new Taliban government has been announced in Afghanistan. What are your first thoughts on looking at the mix?

Rakesh Sood: The new Taliban interim government reflects the internal differences between the Taliban’s different factions, which is why it took them quite some time to come out with the composition.

Second, it was quite clear that getting over these differences needed the presence of the ISI and that is why the DG ISI was physically present in Kabul, meeting different Taliban factions, the leaders and the groups, to be able to work out a compromise.

Taliban Cabinet Ministers | Pic Credit: AP

Akrita Reyar: Taking forward the point of the Pakistan imprint on the new Taliban government, how much of a hand of Pakistan do you see in the entire strategy and execution of the Taliban operation to take over Afghanistan? Was this completely its brainchild?

Rakesh Sood: The Taliban followed a calibrated military strategy. They waited till they were absolutely certain that the US was sticking to a withdrawal deadline and it was an unconditional withdrawal. This was announced by President Joe Biden on the 14th of April. Thereafter, beginning in May, the Taliban executed an effective military strategy. I am sure they had good teachers who had learned the lessons of what had gone wrong in the past during the 1990s. Obviously, the good teachers I’m referring to are the ISI who were advising them. However, the Taliban, I think, were then able to execute this strategy reasonably efficiently. The strategy consisting of focusing on the more isolated military and police outposts, especially in the remote areas, which have a limited strength of maybe 10 to 15 people; it was easy to surround them with 40 to 50 Taliban fighters and since the US was in the process of withdrawal and air support was missing, the 10 to 15 people at these remote outposts ended up surrendering or capitulating because they were promised safe passage. This resulted in the fact that the Taliban were also able to acquire, without much fighting, additional military hardware from the stores at these places.

Taliban soldiers stand guard over surrendered Afghan Militiamen in the Kapisa province | Pic Credit: AP

The second strategy that the Taliban then followed was to move to the northern parts of Afghanistan and certain district headquarters as these were the expected areas of resistance. After they had taken these over, it enabled them to surround certain provincial capitals. They only started focusing on the provincial capitals in August. So through May, June and July, they essentially focused on remote areas, district headquarters, and revenue-generating border checkpoints. They knew that they would perhaps face resistance out of Panjshir valley, so they surrounded Panjshir Valley and cut it off from other districts at the Tajik border. Therefore Panjshir Valley lost its connectivity to Tajikistan, which is what it had retained during the 1990s when the Soviets could not occupy Panjshir Valley or when the Taliban during the 1990s could not occupy Panjshir Valley.

A Taliban soldier guards the Panjshir gate in Panjshir province of Afghanistan | Pic Credit: AP

Akrita Reyar: How do you predict Western nations including the EU and the US to respond to the Taliban government in terms of giving it recognition and future dealings; after all, most are UN-designated terrorists and have bounties on their heads?

Rakesh Sood: I am not in a position to predict how Western governments will respond to it. They will I’m sure take their decisions based on their interests. They obviously want to ensure that they’re able to get not just their citizens, but also the Afghans who have worked with them and they feel that they need to bring them out because they are in a position of vulnerability or danger. So that is one priority for the Western governments. Another priority for the Western governments is to ensure that there is no refugee influx into their countries. I don’t think they will bother too much if the Afghan refugees went to neighbouring countries like Pakistan or Iran, but certainly, they will not want refugees coming into Europe or into Canada or America. Third, I think they would also like, to the extent possible, to prevent any humanitarian crisis arising out of food shortages or medical shortages.

Akrita Reyar: Do the developments have a sobering impact on India? Were we underprepared in the face of imminent US pullout? And what now from here…

Rakesh Sood: I do not know, but I think that any political observer would indicate that the process of legitimization of the Taliban was quite clear for at least a decade, if not earlier. In 2013, the Taliban opened an international office in Doha and they had a public presence. A number of countries were engaging with the Taliban directly, a number of European countries, plus China plus Russia plus Iran plus, of course, Pakistan and Central Asian countries. Taliban delegations were being received in many of these countries. I think it was therefore quite clear that the Taliban was emerging as a political actor. And that was in 2013, in 2018 the US began direct talks with the Taliban. So it should have been abundantly clear then; in 2020 an agreement was signed with the timeline for US withdrawal. It should again have been abundantly clear and as I said earlier, on 14th April, President Joe Biden also announced he would stick to the agreement except that he extended the withdrawal timeline from 30th of April to the 31st of August. So, in short, for nearly a decade, the writing has been on the wall that the Taliban were coming back, and the US was in the exit mode.

U.S. Army, Maj. Gen. Chris Donahue, commander of the U.S. Army 82nd Airborne Division, XVIII Airborne Corps, was the last U.S. soldier to board a C-17 cargo plane at Kabul airport | Pic Credit: AP

Therefore, anybody who says that we were surprised, I think has failed to see the writing on the wall. Yes, you could be surprised about the fact that the actual US withdrawal in the last two weeks was conducted somewhat poorly. It reflected a lack of proper planning or reflected a degree of incompetence, but that is only in the last two weeks with the fact that the US was leaving, and the Taliban were coming back is something that has been known for, as I said, nearly a decade.

Akrita Reyar: We can’t get away from the question of China and Russia – what is it for them in this and how do you foresee them playing their cards? You have already mentioned they have been engaging with the Taliban for a while.

Rakesh Sood: I think both China and Russia, having got rid of the US presence in Afghanistan, will now focus on their interests in terms of the fact, whether the Taliban will keep to their understanding, which the Taliban have conveyed to China and to Russia, that they will address their security concerns and not allow any groups in Afghanistan to adversely target either Chinese territory or Russian territory, I’m sure the Chinese or Russians will see to if these commitments are being fully honoured or not and calibrate their relationship accordingly.